SingletonTrait (New)

Read more at http://www.phpclasses.org/package/9833-PHP-Trait-to-implement-the-singleton-design-pattern.html

In this tutorial we are going to show you how to make a JavaScript photobooth app that takes images using the camera on your phone, laptop or desktop. We will showcase a number of awesome native APIs that allowed us to make our project without any external dependencies, third-party libraries or Flash – vanilla JavaScript only!

Note that this app uses experimental technologies that are not available in desktop and mobile Safari.

To the end user our app is just an oversimplified version of the camera app you can find on any smartphone. It uses a hardware camera to take pictures – that’s it. Under the hood, however, a whole lot of JavaScript magic is going on. Here is a high-level overview:

In the article below we will only look at the more interesting parts of the code. For the full source go to the Download button near the top of this page or checkout the demo on JSfiddle.

Keep in mind that the

navigator.getUserMediaAPI is considered deprecated, but it still has pretty good browser support and is the only way to access the camera right now, until it’s future replacement – navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia gains wider browser support.

JavaScript provides a native API for accessing any camera hardware in the form of the navigator.getUserMedia method. Since it handles private data this API work only in secure HTTPS connections and always asks for user permission before proceeding.

Permission Dialog In Desktop Chrome

If the user allows to enable his camera, navigator.getUserMedia gives us a video stream in a success callback. This stream consists of the raw broadcast data coming in from the camera and needs to be transformed into an actual usable media source with the createObjectURL method.

navigator.getUserMedia(

// Options

{

video: true

},

// Success Callback

function(stream){

// Create an object URL for the video stream and

// set it as src of our HTLM video element.

video.src = window.URL.createObjectURL(stream);

// Play the video element to show the stream to the user.

video.play();

},

// Error Callback

function(err){

// Most common errors are PermissionDenied and DevicesNotFound.

console.error(err);

}

);

Once we have the video stream going, we can take snapshots from the camera input. This is done with a nifty trick that utilizes the mighty <canvas> element to grab a frame from the running video stream and save it in an <img> element.

function takeSnapshot(){

var hidden_canvas = document.querySelector('canvas'),

video = document.querySelector('video.camera_stream'),

image = document.querySelector('img.photo'),

// Get the exact size of the video element.

width = video.videoWidth,

height = video.videoHeight,

// Context object for working with the canvas.

context = hidden_canvas.getContext('2d');

// Set the canvas to the same dimensions as the video.

hidden_canvas.width = width;

hidden_canvas.height = height;

// Draw a copy of the current frame from the video on the canvas.

context.drawImage(video, 0, 0, width, height);

// Get an image dataURL from the canvas.

var imageDataURL = hidden_canvas.toDataURL('image/png');

// Set the dataURL as source of an image element, showing the captured photo.

image.setAttribute('src', imageDataURL);

}

The canvas element itself doesn’t even need to be visible in the DOM. We are only using its JavaScript API as a way to capture a still moment from the video.

Of course, we not only want to take glorious selfies but we also want be able to save them for future generations to see. The easiest way to do this is with the download attribute for <a> elements. In the HTML the button looks like this:

<a id="dl-btn" href="#" download="glorious_selfie.png">Save Photo</a>

The download attribute transforms our anchor from a hyperlink into a download button. Its value represents the default name of the downloadable file, the actual file to download is stored in the href attribute, which as you can see is empty for now. To load our newly taken photo here, we can use the image dataURL from the previous section:

function takeSnapshot(){

//...

// Get an image dataURL from the canvas.

var imageDataURL = hidden_canvas.toDataURL('image/png');

// Set the href attribute of the download button.

document.querySelector('#dl-btn').href = imageDataURL;

}

Now when somebody clicks on that button they will be prompted to download a file named glorious_selfie.png, containing the photo they took. With this our little experiment is complete!

We hope that you’ve learned a lot from this tutorial and that you now feel inspired to build some kick-ass photo apps. As always, feel free to ask questions or share ideas in the comment section below!

Every geek goes through a phase where they discover emulation. It's practically a rite of passage.

I think I spent most of my childhood – and a large part of my life as a young adult – desperately wishing I was in a video game arcade. When I finally obtained my driver's license, my first thought wasn't about the girls I would take on dates, or the road trips I'd take with my friends. Sadly, no. I was thrilled that I could drive myself to the arcade any time I wanted.

My two arcade emulator builds in 2005 satisfied my itch thoroughly. I recently took my son Henry to the California Extreme expo, which features almost every significant pinball and arcade game ever made, live and in person and real. He enjoyed it so much that I found myself again yearning to share that part of our history with my kids – in a suitably emulated, arcade form factor.

Down, down the rabbit hole I went again:

I discovered that emulation builds are so much cheaper and easier now than they were when I last attempted this a decade ago. Here's why:

The ascendance of Raspberry Pi has single-handedly revolutionized the emulation scene. The Pi is now on version 3, which adds critical WiFi and Bluetooth functionality on top of additional speed. It's fast enough to emulate N64 and PSX and Dreamcast reasonably, all for a whopping $35. Just download the RetroPie bootable OS on a $10 32GB SD card, slot it into your Pi, and … well, basically you're done. The distribution comes with some free games on it. Add additional ROMs and game images to taste.

Chinese all-in-one JAMMA cards are available everywhere for about $90. Pandora's Box is one "brand". These things are are an entire 60-in-1 to 600-in-1 arcade on a board, with an ARM CPU and built-in ROMs and everything … probably completely illegal and unlicensed, of course. You could buy some old broken down husk of an arcade game cabinet, anything at all as long as it's a JAMMA compatible arcade game – a standard introduced in 1985 – with working monitor and controls. Plug this replacement JAMMA box in, and bam: you now have your own virtual arcade. Or you could build or buy a new JAMMA compatible cabinet; there are hundreds out there to choose from.

Cheap, quality IPS arcade size LCDs. The CRTs I used in 2005 may have been truer to old arcade games, but they were a giant pain to work with. They're enormous, heavy, and require a lot of power. Viewing angle and speed of refresh are rather critical for arcade machines, and both are largely solved problems for LCDs at this point, which are light, easy to work with, and sip power for $100 or less.

Add all that up – it's not like the price of MDF or arcade buttons and joysticks has changed substantially in the last decade – and what we have today is a console and arcade emulation wonderland! If you'd like to go down this rabbit hole with me, bear in mind that I've just started, but I do have some specific recommendations.

Get a Raspberry Pi starter kit. I recommend this particular starter kit, which includes the essentials: a clear case, heatsinks – you definitely want small heatsinks on your 3, as it dissipate almost 4 watts under full load – and a suitable power adapter. That's $50.

Get a quality SD card. The primary "drive" on your Pi will be the SD card, so make it a quality one. Based on these excellent benchmarks, I recommend the Sandisk Extreme 32GB or Samsung Evo+ 32GB models for best price to peformance ratio. That'll be $15, tops.

Download and install the bootable RetroPie image on your SD card. It's amazing how far this project has come since 2013, it is now about as close to plug and play as it gets for free, open source software. The install is, dare I say … "easy"?

Decide how much you want to build. At this point you have a fully functioning emulation brain for well under $100 which is capable of playing literally every significant console and arcade game created prior to 1997. Your 1985 self is probably drunk with power. It is kinda awesome. Stop doing the Safety Dance for a moment and ask yourself these questions:

What controls do you plan to plug in via the USB ports? This will depend heavily on which games you want to play. Beyond the absolute basics of joystick and two buttons, there are Nintendo 64 games (think analog stick(s) required), driving games, spinner and trackball games, multiplayer games, yoke control games (think Star Wars), virtual gun games, and so on.

What display to you plan to plug in via the HDMI port? You could go with a tiny screen and build a handheld emulator, the Pi is certainly small enough. Or you could have no display at all, and jack in via HDMI to any nearby display for whatever gaming jamboree might befall you and your friends. I will say that, for whatever size you build, more display is better. Absolutely go as big as you can in the allowed form factor, though the Pi won't effectively use much more than a 1080p display maximum.

How much space do you want to dedicate to the box? Will it be portable? You could go anywhere from ultra-minimalist – a control box you can plug into any HDMI screen with a wireless controller – to a giant 40" widescreen stand up arcade machine with room for four players.

What's your budget? We've only spent under $100 at this point, and great screens and new controllers aren't a whole lot more, but sometimes you want to build from spare parts you have lying around, if you can.

Do you have the time and inclination to build this from parts? Or do you prefer to buy it pre-built?

These are all your calls to make. You can get some ideas from the pictures I posted at the top of this blog post, or search the web for "Raspberry Pi Arcade" for lots of other ideas.

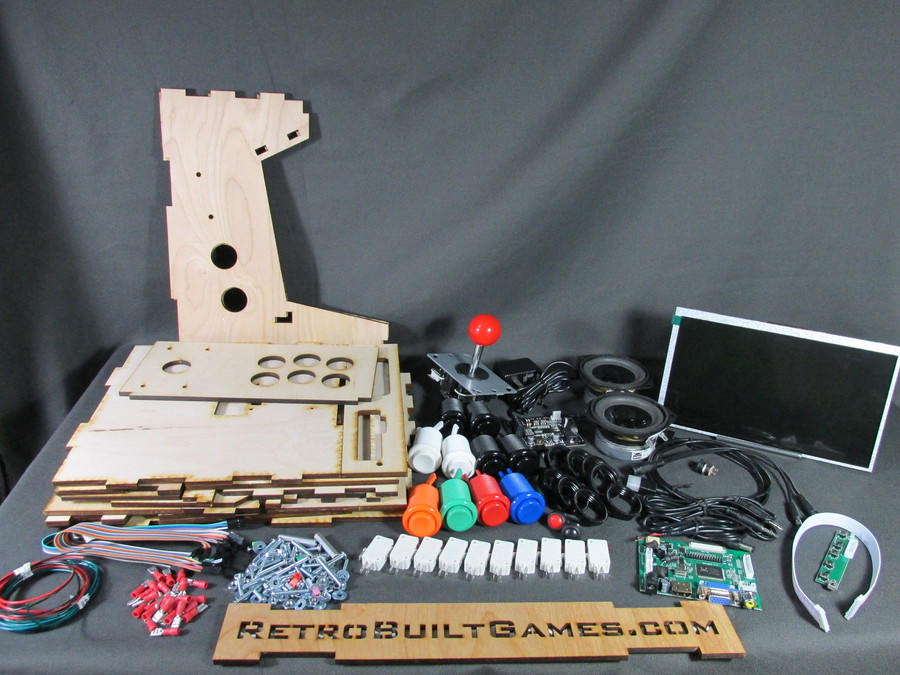

As a reasonable all-purpose starting point, I recommend the Build-Your-Own-Arcade kits from Retro Built Games. From $330 for full kit, to $90 for just the wood case.

You could also buy the arcade controls alone for $75, and build out (or buy) a case to put them in.

My "mainstream" recommendation is a bartop arcade. It uses a common LCD panel size in the typical horizontal orientation, it's reasonably space efficient and somewhat portable, while still being comfortably large enough for a nice big screen with large speakers gameplay experience, and it supports two players if that's what you want. That'll be about $100 to $300 depending on options.

I remember spending well over $1,500 to build my old arcade cabinets. I'm excited that it's no longer necessary to invest that much time, effort or money to successfully revisit our arcade past.

Thanks largely to the Raspberry Pi 3 and the RetroPie project, this is now a simple Maker project you can (and should!) take on in a weekend with a friend or family. For a budget of $100 to $300 – maybe $500 if you want to get extra fancy – you can have a pretty great classic arcade and classic console emulation experience. That's way better than I was doing in 2005, even adjusting for inflation.

| [advertisement] At Stack Overflow, we put developers first. We already help you find answers to your tough coding questions; now let us help you find your next job. |